The Significance and Strategies of Translation

and Interpretation Courses in Teaching

Korean as a Foreign Language

Interview with Professor Lim Hyung-jae of the

Department of Korean as a Foreign

Language Translation, Hankuk University

of Foreign Studies

On September 14, during KSIF’s Online Workshop for KSI Teachers in English-speaking Regions on Translation and Interpretation Curriculum, Professor Lim Hyung-jae delivered a lecture on “The Significance of Translation and Interpretation Courses in Teaching Korean as a Foreign Language.” We spoke with Professor Lim to learn more about the value of translation and interpretation courses in Korean language education in the age of artificial intelligence (AI) and how they can be applied in real classroom settings.

Hello, Professor Lim Hyung-jae. Thank you for joining us for this interview. To begin, please introduce yourself to the readers of Monthly Knock Knock and tell us about your research and teaching areas.

Hello. My name is Lim Hyung-jae, and I teach and conduct research in the Department of Korean as a Foreign Language Translation at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies. My research focuses on establishing a systematic framework for Korean translation and interpretation education for foreign learners. In particular, I explore ways to integrate Korean language education as a foreign language with specialized translation and interpretation training, as well as the evolving roles of translators and interpreters in the age of AI.

In my classes, I provide AI-based translation and interpretation training grounded in an understanding of translation studies for foreign learners of Korean. Recently, I have also been devoting attention to enhancing the competencies of Korean language teachers who wish to incorporate translation and interpretation education into their teaching. In addition, I am involved in developing textbooks and training models to foster future Korean translators and interpreters. Moving forward, I aim to continue conducting field-oriented research and education so that Korean translation and interpretation education across various language regions can be applied effectively in real-world contexts.

Professor Lim Hyung-jae delivering a special lecture during the June Online Workshop for KSI Teachers on Translation and Interpretation Curriculum in Vietnam

Professor Lim Hyung-jae delivering a special lecture during the June Online Workshop for KSI Teachers on Translation and Interpretation Curriculum in Vietnam

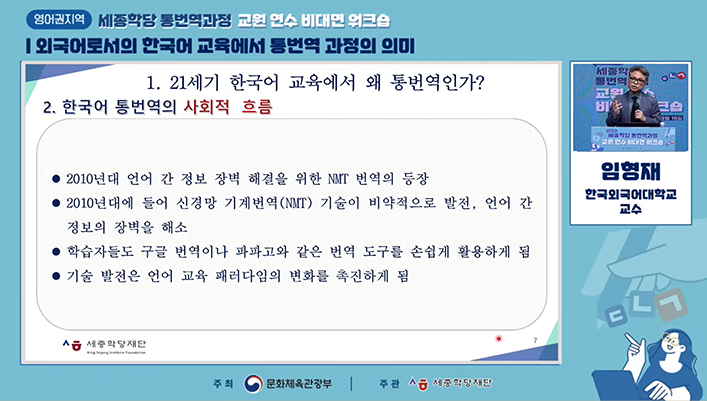

On September 14, you delivered a special lecture titled “The Significance of Translation and Interpretation Courses in Teaching Korean as a Foreign Language” during the Online Workshop for KSI Teachers in English-speaking Regions on Translation and Interpretation Curriculum. What key themes did you focus on in your lecture?

This lecture began with the question, “Why should we discuss translation and interpretation education in the 21st century, in the age of artificial intelligence (AI)?” In today’s globalized and digitally innovative environment, translation and interpretation are being redefined—not merely as linguistic conversion, but as intercultural mediation or bridging competence. I first emphasized that the spread of the Korean Wave, the global expansion of Korean companies, and the emergence of multicultural and multilingual societies have significantly broadened the scope and increased the necessity of translation and interpretation between Korean and other languages. I then introduced translation and interpretation as the fifth linguistic skill—in addition to reading, writing, listening, and speaking—calling it “transfer.” Through this, I explained that Korean language learners can grow into mediators who facilitate communication between languages and cultures.

Next, based on the Process of Acquisition of Translation Competence and Evaluation (PACTE) model and the European Master’s in Translation Competence Framework (EMT), I highlighted that a learner’s translation and interpretation competence is multidimensional. It encompasses not only linguistic ability but also cultural understanding, information literacy, strategic decision-making, and tool utilization skills. From an educational perspective, I presented various classroom activities—such as pedagogical translation, interpretation role-playing, and post-editing of machine translation—as effective ways to foster learners’ critical thinking and metalinguistic awareness, illustrating each with specific examples.

Finally, I outlined the goals of the KSI Translation and Interpretation Curriculum: to provide practical and adaptive training for intermediate and advanced learners, to expand cultural understanding, to strengthen teachers’ competence in teaching translation and interpretation, and to cultivate globally minded cultural mediators. I emphasized the importance of KSI teachers sharing this vision and incorporating it into their lesson design.

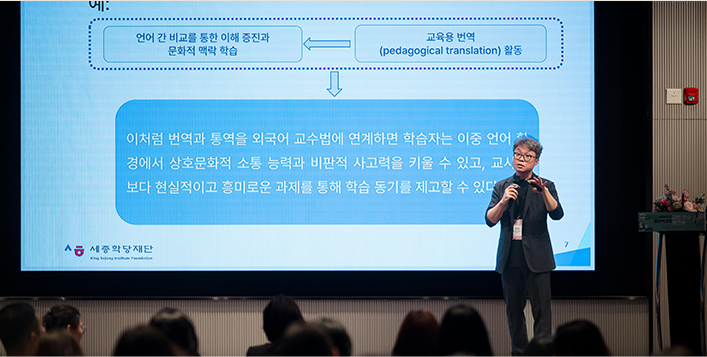

Professor Lim Hyung-jae delivering a special lecture during the September 14 Online Workshop for KSI Teachers in English-speaking Regions on Translation and Interpretation Curriculum

Professor Lim Hyung-jae delivering a special lecture during the September 14 Online Workshop for KSI Teachers in English-speaking Regions on Translation and Interpretation Curriculum

How can the topics covered in this workshop be applied in Korean translation and interpretation education at KSIs in English-speaking regions? What should KSI teachers keep in mind to use these methods more effectively in their actual classes?

KSI teachers in English-speaking regions constantly consider how to implement “Korean-centered translation and interpretation education” while taking into account their learners’ linguistic backgrounds and classroom environments. With this in mind, the workshop discussed concrete teaching and learning strategies that can be applied directly in the classroom.

First, there is the target-language-based instructional strategy. Korean teachers can effectively lead translation and interpretation classes without relying on learners’ native languages. The key is to train students to analyze Korean source texts into semantic units (semantic chunking) and select appropriate strategies—such as literal translation, free translation, insertion, or omission—depending on the reader and the translation purpose. For instance, when translating a short notice, learners can compare literal and free translation versions and discuss which one better suits the target reader. This approach, grounded in functionalist theory, helps learners strengthen their understanding and awareness of the translation process and its purpose.

Second, teachers should make active use of AI and digital tools. English-speaking learners frequently use large language models (LLMs) and neural machine translation (NMT) tools such as ChatGPT, Gemini, Google Translate, and Papago. Rather than discouraging their use, teachers should integrate these tools pedagogically—guiding learners to critically analyze machine translation outputs and perform post-editing. Through this process, learners gain a deeper understanding of what makes a good translation, learn the principles of language transfer, and develop critical information literacy.

Third, a step-by-step approach to interpretation training is essential. The workshop introduced practical models such as shadowing, listening and summarizing, and reverse rendition. For example, a learner listens to a short Korean utterance, summarizes the key points in English, and then another learner reconstructs it back into Korean. This allows teachers to indirectly assess students’ comprehension and identify any missing information.

Fourth, team teaching and collaboration with local teachers are highly effective. When Korean teachers and local English-speaking teachers work together, translation and interpretation classes become more dynamic. Korean teachers can focus on text analysis and translation strategies, while local teachers can refine English expressions and address cultural nuances. Such collaboration provides learners with two-way feedback and helps them develop balanced mediation skills between languages and cultures.

Therefore, KSI teachers in English-speaking regions can achieve more effective outcomes by combining target-language-based instruction, AI and computer-assisted translation (CAT) tools, stepwise interpretation training, and collaborative teaching models. Most importantly, learners should not stop at simply producing translated results—they should be guided to articulate and reflect on the purpose, strategy, and cultural context behind their translations.

Professor Lim Hyung-jae delivering a special lecture on “The Significance of Translation and Interpretation Courses in Teaching Korean as a Foreign Language” during the workshop

Professor Lim Hyung-jae delivering a special lecture on “The Significance of Translation and Interpretation Courses in Teaching Korean as a Foreign Language” during the workshop

In your view, what kinds of institutional or policy support are most needed to effectively operate translation and interpretation programs at KSIs in English-speaking regions?

To ensure the stable operation of translation and interpretation programs at KSIs in English-speaking regions, institutional and policy support is essential. I would like to highlight four key areas.

First, systematic training programs to strengthen teacher competencies. Translation and interpretation education differs from general Korean language instruction in that it requires bilingual proficiency and intercultural mediation skills. However, not all teachers have received professional translation and interpretation training. Therefore, KSIF should establish regular professional development programs for KSI teachers to help them acquire practical knowledge in translation studies, teaching methods, assessment standards, and the use of AI-based tools. A combination of online lectures, mock classes, and mentoring would be particularly effective in achieving this goal.

Second, the distribution of standardized textbooks and assessment tools. Although KSIF has developed teaching materials, there are still few that fully reflect the linguistic and cultural characteristics of English-speaking learners or that are tailored to learners’ individual proficiency levels. For example, specialized fields such as law, medicine, and business require distinct case studies and vocabulary. Hence, developing modular textbooks that address these differences is necessary. In terms of assessment, a rubric-based evaluation system is needed to ensure objective and consistent grading based on clearly defined criteria and proficiency levels. In particular, developing AI-assisted quantitative assessment tools and qualitative evaluation models—such as those based on Multidimensional Quality Metrics (MQM) or the ISO 5060 General Guidelines for Translation Quality Assessment—would allow teachers to more reliably evaluate and provide feedback on learners’ performance.

Third, the establishment of a learner data collection and sharing platform. There should be a global platform where KSI teachers can systematically accumulate and share data on learner translation errors, interpretation performance records, and exemplary teaching practices. Beyond simple information exchange, such a platform could also be utilized to develop AI-powered teaching tools based on large language models (LLMs). In particular, an “automated feedback system based on learners’ actual translation outputs” could reduce teachers’ workload while helping learners engage in self-assessment.

Fourth, sustained policy-level funding support. Translation and interpretation education is directly linked to practical fields such as tourism, business, and public services in local communities. Therefore, with appropriate financial support, KSIs could collaborate with local public institutions and universities to conduct project-based learning programs connected to real-world professional contexts. Such initiatives would allow learners to gain hands-on experience while contributing to the local community—realizing the vision of “living education” that bridges classroom learning and societal engagement.

Finally, as KSIs around the world operate Korean translation and interpretation programs tailored to the diverse needs of local learners, what educational approaches or strategies would you recommend to help beginner and intermediate learners naturally progress to advanced levels and ultimately to translation and interpretation training?

For beginner and intermediate learners to advance to higher proficiency and eventually transition into translation and interpretation training, it is essential to design an integrated curriculum that connects the stages of Korean language education → Korean for translation and interpretation purposes → translation and interpretation training.

First, it is important to establish a natural connection between language skill learning and translation activities. For example, in a reading class, learners can try translating simple sentences into their native language, or in a speaking class, they can engage in short interpretation role-plays. Through such activities, learners come to perceive translation and interpretation not as separate professional skills but as an extension of their Korean language learning.

Second, a gradual adjustment of difficulty is necessary. At the beginner level, tasks may involve translating simple notices, signs, or everyday conversations. At the intermediate level, materials can expand to include news articles or short interviews. At the advanced level, the curriculum should progress to specialized texts and project-based learning, allowing learners to engage in real-world translation and interpretation practice. In this way, translation and interpretation become fully integrated learning models, leading naturally into Korean language education for translation and interpretation purposes.

Third, mechanisms to sustain learner motivation are crucial. Many intermediate and advanced learners experience stagnation or a loss of motivation once they achieve functional fluency in Korean. In such cases, participating in real translation and interpretation projects, creating portfolios, or engaging in error correction and post-editing activities can help them experience a sense of professional relevance and accomplishment. This, in turn, serves as a strong driving force for continued learning.

Fourth, deeper cultural understanding and critical thinking training must accompany language and translation instruction. Translation is not simply a linguistic transfer but an act of mediating context and culture. Therefore, learners should be continually exposed to cultural elements that require special attention in translation, speech act strategies (ways of re-creating the original intent of utterances in accordance with the target culture’s norms), and social discourse. Through these processes, learners can grow into mediators of linguistic and cultural exchange and naturally progress toward advanced-level translation and interpretation training.